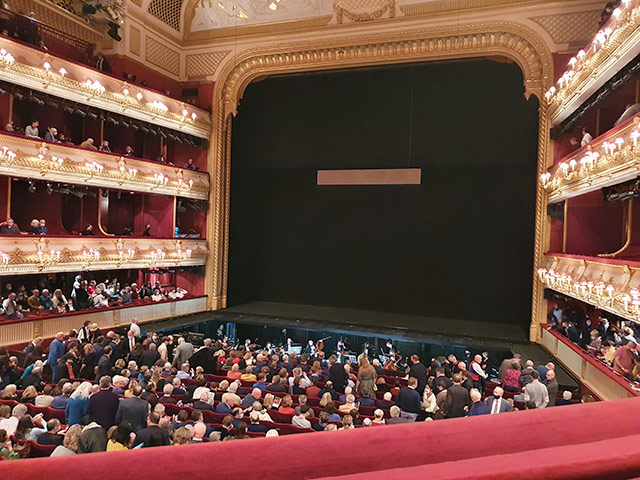

Haendel’s Theodora, the performance, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

A major Handelian work is being performed at Covent Garden from 31 January to 16 February, directed by Katie Mitchell and starring notably Julia Bullock, Jakub Jozef Orlinski and Joyce DiDonato. Various reviews are available, more or less laudatory, many of which agree in pointing out a striking gap between Haendel's music of the 18th century and the modern story that tries to bring it to us. So much so that one of them declares that this show is like a film whose soundtrack has nothing to do with it.

Perhaps this is relatively accurate, and perhaps it is assumed by the production?

In that case, why not? Those who, like Katie Mitchell, bring to life in such a place, such a formidable musical institution, a music that has not resounded there since it was created by its author in 1750, deserve already some gratitude. Such an intention can makes us realize how great music is a sound that travels thanks to those who play it, just as great concepts of language travel thanks to those who enunciate and represent them. The musical force of this work, exceptional achievement of an exceptional artist, makes it feel, the gap with its film also.

Theodora, therefore, which Haendel is said to affectionate, comes to us in a staging that is announced as feminist, but Thomas Morell's libretto of 1749, based on R. Boyle and Corneille and therefore according to Haendel's wish, was already so.

The legend of Theodora and Didymus, lovers martyrs of the Christian cause under the Roman occupation, is known from the 4th century on - this Roman officer rallied to the cause and love, to the cause of love, was showing there an even greater heroism than his girlfriend. It was moved from Alexandria to Antioch, the high place of Christianity and resistance to the empire, known for the mission of Paul of Tarsus who took off there, and for its revolt against the imperial statues, which was severely punished before an earthquake finally destroyed its splendor. An earthquake contributed also to the historic failure of the Covent Garden premiere of Haendel's Theodora, before blindness progressively stopped the composer's fruitful work.

No feminism today would disavow this legend, without the need to add to it the handling of bombs and guns in the kitchen by our radicalized believers, nor to exult at the idea that before dying they would kill their executioners, although these comical additions by Katie Mitchell aim to serve a just cause, which is still current. Is not Didymus, this Roman hero, who abandons the beliefs of his camp to support and adhere to the cause of his beloved, whom he takes as his guide, already the angel of an eternal revolution? Is Theodora not already imbued with that deep feminism which sometimes makes a couple of lovers the natural ground of its revolution, in a context where the Roman patriarchy was not in the habit of joking with the proper ordering of things and sexes? Is it not already profoundly feminist, this drama which in Morell's own libretto includes a clothing exchange between the man and the woman in order to save her from the prostitution to which she is condemned, was it dedicated to Venus?

The show takes a long time for it to carry you away, after the strange beginnings of this staging which makes the voices sing far from their audience and sometimes makes them barely audible. Joyce DiDonato on the contrary fills the stage and the auditorium with her own voice without ever fading away. That special honey she distills in the nice roundness of her voice, the limpidity, the clarity of her tone and speech, her perspicacity, always make her find the scale and the place to reach her audience, a great lady of singing, really. Julia Bullock enchant us with the accuracy of her singing - in enchanting there is singing in French, so it is a nice language - her exact crystal in all her utterances, her measure too, which however does not hesitate in front of the rivers of imperious notes that Haendel's score prescribes.

Although Didymus sings almost as soon as the curtain opens, Jakub Jozef Orlinski takes longer to join us, as if he were a bit of a step back at first in this living room, where he seems to be whispering his prayer to Valens from behind the scenes. As if he were still preparing what will become his next voice, the one that will carry us away definitively on the second act. As if, surrounded then by such voices, his own grew even more and took off. The music of the second act is for him a jewel that he knows how to seize, that his voice will never more let go of. It culminates in the marvelous duet with Bullock's, where truly all of Haendel's singing resounds endlessly carried by these singers who know how to inhabit it and love to. The applause is unavoidable here too, and bears witness to a rare happiness.

At the climax of this act, the brothel scene features Jakub-Didymus in a glittering dress, a blonde wig and high shoes, performing a hypnotic pole dance several times in imitation of the residents of the brothel. And this dance becomes the very word of despair, his pathetic yet graceful gestures make the hero empty to the lees the chalice of transvestic that he has to incarnate. A poignant scene in which musical beauty trembles against the excess shown to us, putting us on the verge of oscillating between an indignant refusal and exhausted consent, to this extreme which makes such grace rise from the very bosom of abjection.

We can measure the gap that Katie Mitchell has established between this divine music, whose libretto already includes the exchange of clothes, and the hallucinating pole dance of Jakub, where the usual comic aspect of the transvestite gradually disappears to make way for the grace that the dancer brings to life almost as if he were a woman, almost better than if he were, in a less provocative way than the women who danced it just before him. In all this, an exceptional music holds us, like a text from the depths of the centuries, the kind of music that at a given moment, really given, implants on your lips a smile of happiness that will remain there, irrepressible, until the curtain falls for the last time.

And far from you the idea of a soundtrack cut from its film, you feel, on the contrary, gratitude for those who have allowed this jewel of Handel to come to you, in the very place where it failed three centuries ago in misunderstanding, when his writing was about to stop. The long applause that here again sprang up as if irrepressible, from an audience that was nonetheless discreet and knowledgeable, makes you feel that you are not alone in feeling it.

The voices of Ed Lyon's, the clear tenor of Septimus the friend, of Gyula Orendt's, the rough bass of Valens the executioner, take their place without fault and structure each act like a presence that brings us back to the earth of the drama. The chorus, though so important on the same path, do not appear as decisive, which is a pity.

What can be said of the third act, which takes us delighted to the end of this hard-won perfection? A dazzling duet of the lovers lulls us again like a gift, which does not come from heaven but from below, when the embracing couple is on its knees and then on the ground, in a strong symbol of what it undergoes and of what it represents. Its sublime song, mixing the two voices in a unique and unreal sound, permanently inscribes in you the very song of Haendel.

Yes, there was a controversy about the supposed sexual and criminal violence of this production, but it’s really irrelevant as the questions it asks and the answers it provides are elsewhere. This film has no soundtrack, on the contrary it is the house and the vehicle of this huge music which it brings once again to life, with a new trip among us, not failing to enchant us this time, carried by great voices that find all its strength of melody. This film does not want to be beautiful, it wants to leave all the beauty to the music, with the exception of one scene which condenses the secret. And Katie Mitchell knows that the trivial kitchen apron with which Joyce and Julia are long dressed could have been forgotten without damage.